search

In November 2022, Houghton Biology professor Dr. Eli Knapp ’00 visited two incredible alumni using their gifts as scholar-servants in Cambodia. The article that follows shares some of his reflections in the weeks after that trip.

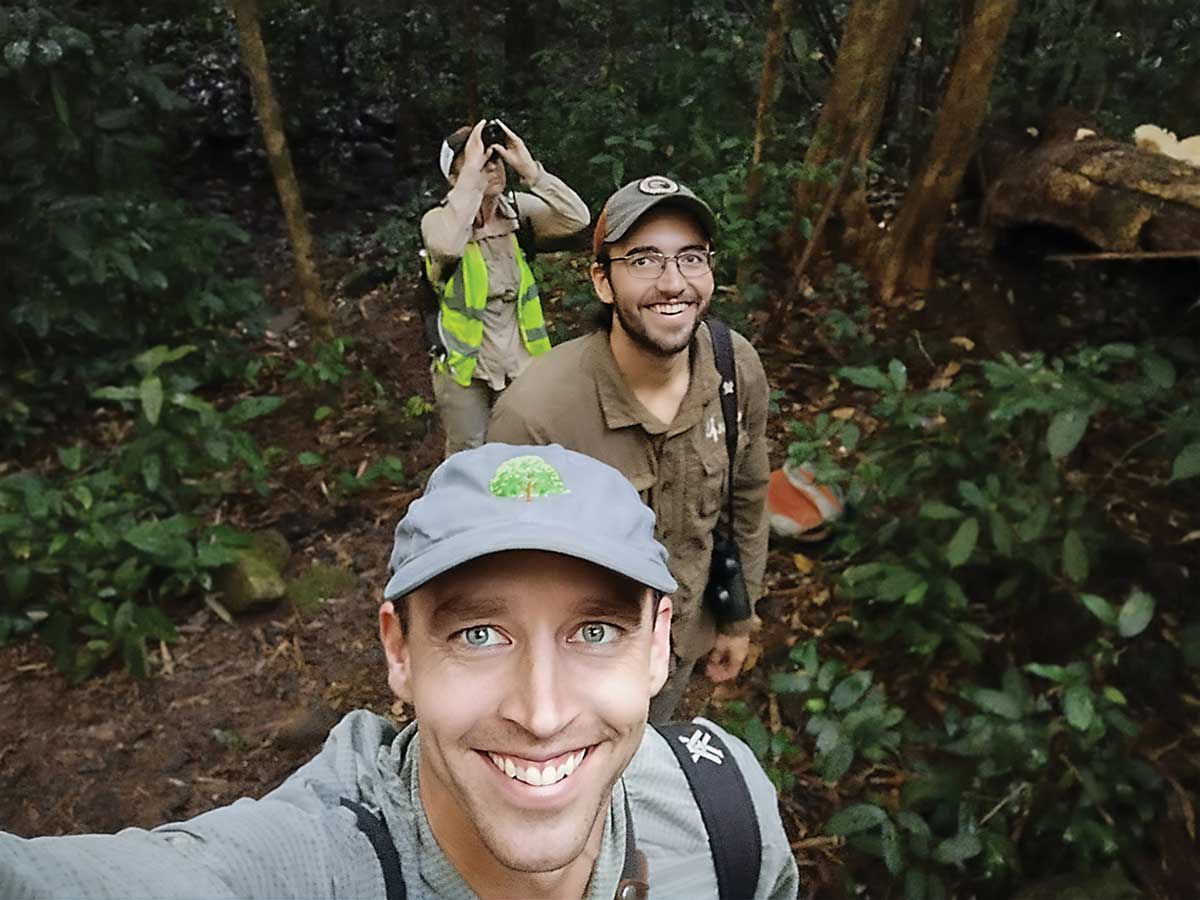

When Jesus admonished the “stiff-necked generation,” he wasn’t talking about gibbon watchers – but He sure could have been. I had spent the last two hours in the Cambodian jungle, head back and chin up, watching long-armed, tailless gibbons brachiate through the branches aware of yet unconcerned with our presence below. Trailing a film crew, my only job was to be quiet and keep out of the way; I fell woefully short of both tasks. How could I remain silent? Above us swung creatures that recent Houghton University graduate Kyle Burrichter ’21 had spent the last two years habituating, a multisyllabic term for teaching the gibbons we didn’t mean any harm. Unlike Cambodian hunters, who historically used gibbons for food, we were there merely to ogle. Around us, these heavily endangered primates could chill out and hopefully sing.

We had been peering into the canopy ever since the first stabs of sunlight penetrated the dark, leafy canopy. Unlike me, the three-person film crew—Humble Bee productions, a subsidiary of the BBC—had been out running about the forest for a month, chasing high-quality, unobstructed shots of the Southern Yellow-Cheeked Crested Gibbon, a wary species renowned for their operatic singing ability, which they typically exercised at dawn, though unpredictably enough to frustrate filmmakers. Since the hoped-for documentary focused on animal vocalization, recording the song wasn’t enough. The crew wanted footage of the process, gape-mouthed gibbons with notes ringing out. For a month, they had struck out, the foliage too thick, the trails too narrow and the gibbons too fickle. With the budget exceeded and only a few days left to film, nerves were tight.

As a visiting Biology professor from Houghton University, I had little business tagging along. Kyle Burrichter, on the other hand, had every reason to be. Through a unique partnership linking Jahoo Gibbon Camp, World Hope International and Houghton University, Kyle had landed an internship with crazy requirements: learn the Khmer language, create trails in the forest, build bird blinds, lead ecotours and, most importantly, habituate the gibbons. While talented Houghton alumni have gone on to do many unique things, none have done this. Outside of Jane Goodall and a handful of dedicated primatologists, few people have ever done this.

For a calendar year, Kyle indefatigably arose in his dank, porous tent at 5 a.m., laced up his sneakers, and plunged into a forest with little more than a headlamp, mosquito coil and a few sleepy Cambodian guides with whom he didn’t share a language. Slowly but surely, the gibbons accepted their bipedal followers, eventually allowing tourists, the film crew and now lucky me to watch them as well.

When Humble Bee productions notified Jahoo about their intention to film gibbons, Kyle was the perfect person to assist. Indispensable, in fact, as he was the only person who knew every trail and every gibbon proclivity and could translate between the local guides and filmmakers.

Useless in the forest and Cambodia at large, I basked in the moment nonetheless. Unfurling before me was the joy of every professor: the chance to watch a freshly minted protégé put academic learning to good use. The only thing I’d done was recognize talent and stoke Kyle’s passions. As the precocious son of colleague Bill Burrichter ’92 , I’d gotten to know Kyle well over his four years at Houghton, having had him in many courses. He’d studied with me in Kenya and taken my ornithology course that traveled to Big Bend National Park, Texas. On that trip, a freak storm whipped up one night and collapsed several tents. While I cowered in my tent, Kyle ran around the campsite propping up tents, tightening guylines and encouraging sopping-wet students. Here was a Houghton student built for something tough.

What I hadn’t anticipated was that the perfect something would present itself just a few years later, through an internship opportunity in the mountainous jungle of eastern Cambodia. Even better, I hadn’t anticipated crossing paths with a second exceptional student who was kind, self-reliant and Christ-loving, tailormade for taking the torch from Kyle.

…he was the only person who knew every trail and every gibbon proclivity and could translate between the local guides and filmmakers.

I got to know Kelly Mohnkern ’22 much the way I had Kyle. Kelly came to Houghton for far more than just accruing credits. She came to leave a mark. In addition to her double major in Intercultural Studies and Biology, Kelly joined the maintenance department, often flying by me in one of Houghton’s utility vehicles as she completed work-study tasks. Each summer, she found employment in a far-flung national park and quenched her thirst for adventure by studying – as Kyle had – in Kenya with me.

In Cambodia, Kyle set the bar high. The gibbons were habituated, trails improved and ecotourism rising. In the fall of ’22, much to my delight, Jahoo Camp and World Hope were ready for another Houghton student, one focused more on community outreach. Again, the job called for a head-scratching assortment of skills: language and computer literacy, hospitality, motorcycle riding, trail maintenance, self-reliance, and the grace to share a tent with a dizzying number of invertebrates—and the occasional snake—for weeks at a time. Kelly, comfortable with cold showers and calloused hands, was just such a person.

For the past six months, Kelly has accomplished her tasks in Cambodia with panache. She is already speaking Khmer, improving trails, leading tours and building local capacity. None of it is easy, and, unsurprisingly, her responsibilities have mushroomed. I’m partly to blame. No longer content to sit on the sidelines, I’ve asked her to help me with a human-ecological research project, both as a way to advance the Houghton–Jahoo–World Hope partnership and as a way to learn about the pressures facing both the gibbons and the local people. Kelly’s research will lead her into Cambodian homes where she’ll sit face to face with local people as she slowly teases out how they utilize the surrounding forest. Finding connections between the human and ecological worlds is difficult but immensely rewarding. It leads you into the lives of fascinating people and only rarely leads to a stiff neck.

Which leads me back to that pressure-packed morning with Kyle, the Cambodian guides and the film crew. After an hour of quiescence, Kyle’s radio crackled to life. He listened intently, mumbled a few words back in Khmer and motioned for us to follow as he sprinted down the trail. Heavy with gear, the film crew galumphed after him, already able to hear the nearby notes of the gibbons. I grabbed somebody’s forgotten backpack and brought up the rear.

Rounding a bend, we all found Kyle pointing up, a look of urgency on his face.

This was the best place for footage, and the singing could stop at any moment. One hundred feet up, a charcoal-colored gibbon with yellow cheeks and an ebony mohawk perched on a stout limb. He grabbed two nearby branches, threw his head back and boomed out an ascending series of notes that augmented a growing chorus all around him—singing! Lightning fast, the crew had tripods out and cameras rolled. Far off gibbons joined in, and the forest became a light-enshrouded cathedral reverberating with song. The moment felt holy.

The ethereal rendition enveloped and transported me, lifting me above my gnawing hunger, jetlag, mosquito bites and even my aching neck. Just a few months removed from the experience, I’ve already forgotten a few particulars. But there’s one thing I won’t forget: how privileged I felt to be following this freshly minted Houghton alumnus, the first – and maybe the last – person to habituate Southern yellow-cheeked crested gibbons.

close

keyboard_arrow_left keyboard_arrow_right

close

keyboard_arrow_left keyboard_arrow_right

close

keyboard_arrow_left keyboard_arrow_right

close

keyboard_arrow_left keyboard_arrow_right

keyboard_arrow_left Next PostPrevious Postkeyboard_arrow_right

Recent Articles